The complete cloud analytics and data platform

Harmonized data and trusted AI/ML for all

lock_open

Unlock data

Empower everyone across the organization to innovate faster by easily unifying and harmonizing all your data.

analytics

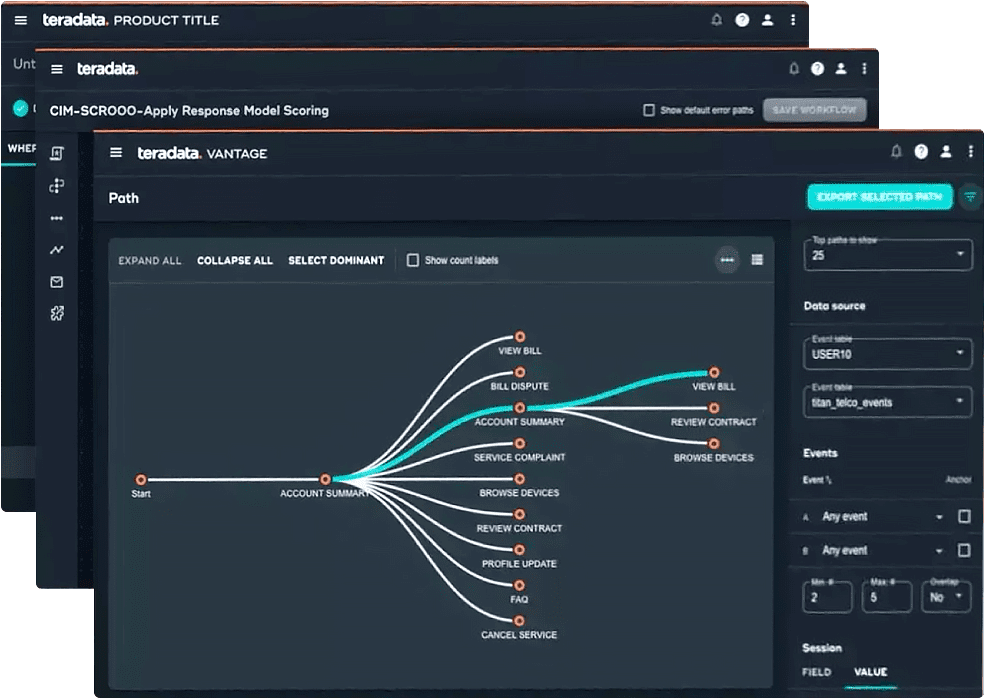

Activate analytics

Transform your data into insights that drive breakthroughs again and again with powerful, integrated AI and cloud analytics.

show_chart

Accelerate value

Fuel your most valuable growth opportunities with AI/ML innovation and cost-effective cloud-native technology that scales elastically.

How we help

Making cloud analytics and data perform better for you

Drive more performance, innovation, and cost efficiency

- Improve resource management

- Activate data-driven decision-making

- Innovate across the enterprise

Simplify and modernize your technology stack

- Connect everything

- Enable flexibility

- Streamline governance

Unlock infinite opportunities from your data universe

- Unlock insights

- Improve predictions

- Reduce time to value

Innovate with unlimited intelligence

- Use your tools of choice

- Simplify your AI operations

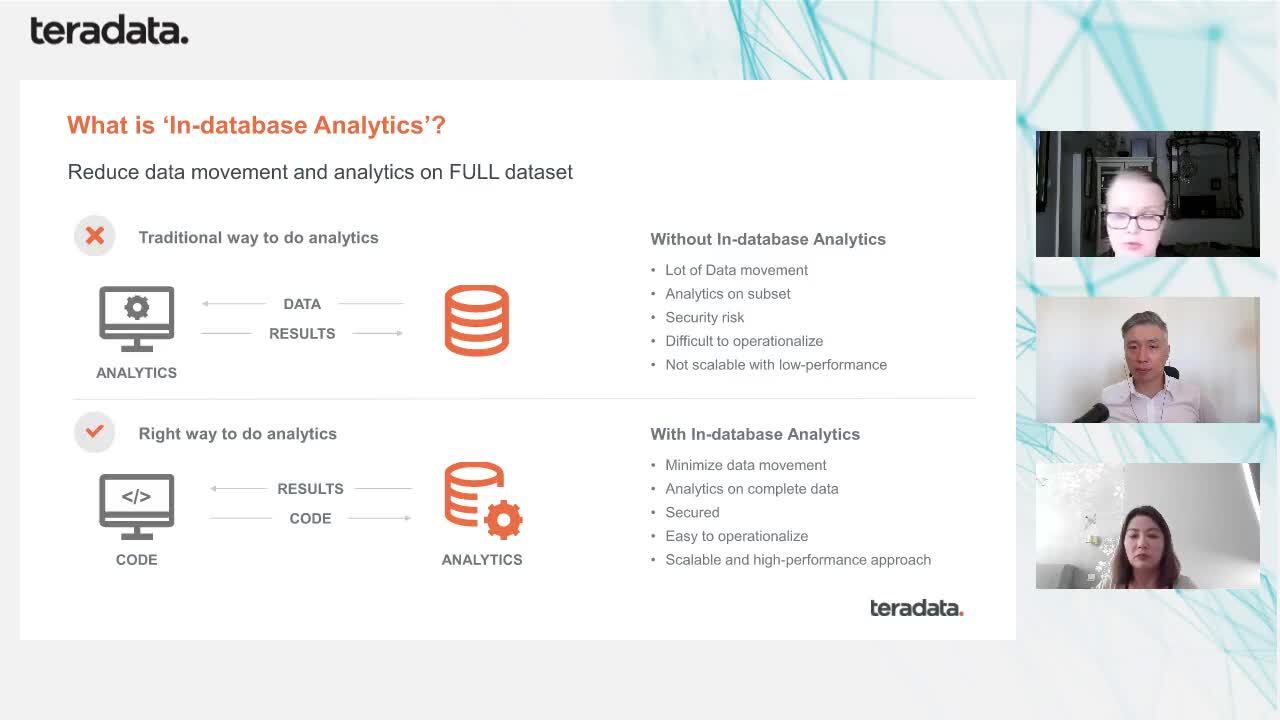

- Innovate with zero data movement

Deliver harmonized data for all

- Control costs

- Improve access

- Simplify data management

Discover a better way to build amazing things

- Power AI innovation

- Enjoy easier collaboration

- Develop solutions faster

Success stories

Leading companies innovate with Teradata

Cloud analytics partners

Better together: Grow your business with our extensive partner community

Discover greater possibilities with our network of over 100 partners. Get the unmatched expertise you need to cultivate your best cloud analytics solution.

Fast-track innovation with generative AI-powered data insights

Accelerate insights, boost productivity, and empower better decision-making.

Insights

Your next breakthrough awaits

Build your future faster today with Teradata VantageCloud

- Accelerate insights and value with harmonized data

- Delight customers with more relevant experiences

- Deliver more breakthroughs with effortless AI